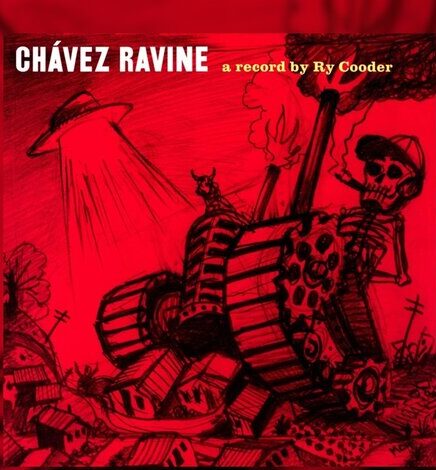

Originally published June 6, 2020 on Albumism

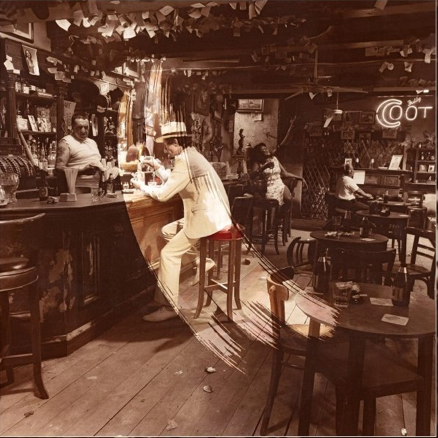

Ry Cooder’s Chávez Ravine was the first solo album he released since 1987’s Get Rhythm and the most ambitious project he was involved in since Buena Vista Social Club in 1997. It’s a history lesson disguised as a Chicano/Tex-Mex/Latin jazz concept album. Better known today as the area where Dodger Stadium is located, Chávez Ravine was a semi-rural neighborhood mostly populated by Mexican American families. Because of racial housing discrimination throughout the city of Los Angeles, many members of this farming community were forced to move to this area. Even though many people depicted Chávez Ravine as an example of urban decay, many of its residents owned their own homes and it became a tight-knit community.

Cooder’s album tells the story of the residents of Chávez Ravine who were systematically being driven away from their homes to make way for what was intended to be integrated public housing. Chávez Ravine tells this story through the eyes of the people who lived there, those who had a hand in relocating these families, and the unfortunate souls who were collateral damage. Many families, for years, had resisted the efforts of the city to evict them. But eventually, the local government used eminent domain to forcibly remove the final holdouts. Not only was a close-knit neighborhood bulldozed, but its vibrant Latino culture was all but erased as well. Set in 1950s Los Angeles, Chávez Ravine is a 15-track opus celebrating and mourning the callous eradicating of a community.

Chávez Ravine opens with “Poor Man’s Shangri-La,” a tale describing the different types of people living in the neighborhood. If it were a movie, it would be the opening credits, with Cooder’s voice relaying the narrative, “He don’t have no uptown friends, or drive a Cadillac / But he’s got cool threads and a beat-up car / All his downtown friends like me ride around in the back / ‘Cause he’s a real cool cat, yeah he’s a real cool cat / This friend of mine La Loma boys will run with you / Do anything that you want them to / If you need a friend ’cause you’re feeling blue / Palo Verde girls never let you down / Na na na na na, living in a poor man’s Shangri-La.” “Poor Man’s Shangri-La” paints a lovely picture of a small community growing through the motions of everyday life, unsuspecting of the nightmare that was ahead of them.

One of my favorite tracks is “Don’t Call Me Red,” about a man named Frank Wilkinson, who represented the Los Angeles Housing Authority in their efforts to tear down what they called sub-standard housing and replace it with public housing. A group of real estate developers thought that building a ballpark would be better suited for the area. At a public hearing deciding the fate of Chávez Ravine, Wilkinson’s well-intentioned plan came to a screeching halt when lawyers for the developers presented an FBI dossier which led to them to ask him his political affiliations. He refused to answer. Wilkinson was branded a Communist, the public housing project was eventually scrapped and he lost his job. He was persona non grata.

The real Frank Wilkinson appears on the track and it is fascinating to hear him recount what happened. There are so many layers to this adventurous track and after multiple listens, I always keep finding something new in lines like, “Every church has its prophets and its elders / God will love you if you just play ball, that’s right / Fritz Burns, Chief Parker, and J Edgar / I outlived those bastards after all / We survived those dark days full of danger / In the end fate has been good to me / If you\’re in the neighborhood, stranger / You’re welcome to drop in and see / My name is Frank, don’t turn me down /Don’t call me red.”

The beauty of Chávez Ravine is how it unfolds like a novela with the stories being told from many different perspectives. “In My Town,” “Barrio Viejo,” and “3rd Base, Dodger Stadium” represent the different stages of the destruction of the neighborhood. “Barrio Viejo” is the sad and mournful tale of the people who stayed behind until the bitter end when they were forcibly removed from their homes and their houses bulldozed. “3rd Base, Dodger Stadium” is told through the eyes of a former resident of Chávez Ravine who now works as a parking attendant at Dodger Stadium. He fondly reminisces about the neighborhood as he gazes over the baseball diamond, imagining where the houses would be: “In the middle of the 1st base line, got my first kiss, Florencia was kind / Now, if the dozer hadn’t taken my yard you’d see the tree with our initials carved / So many moments in my memory. Sure was fun, ’cause the game was free / It was free.”

Despite being nominated for a GRAMMY awards for Best Contemporary Folk Album in 2006, Chávez Ravine is one of those albums that kind of got lost in the early oughts and that\’s a shame because it’s a very good album that tells the tale of the neighborhood and its inhabitants who have been long forgotten. After hearing the album for the first time and reading more about Chávez Ravine, I’ve never been able to look at Dodger Stadium the same way again and it’s been fifteen years.