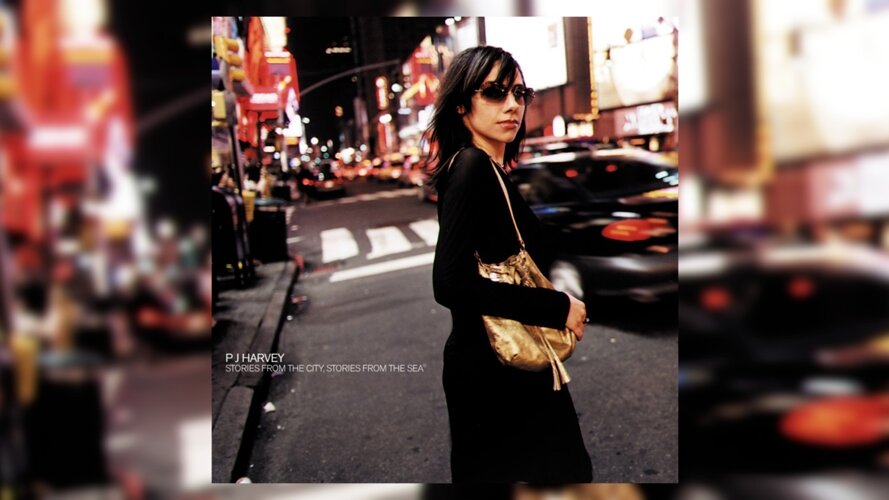

Happy 45th Anniversary to David Bowie’s tenth studio album Station to Station, originally released January 23, 1976. Originally published at Albumism January 21, 2021

German author Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote that genius and madness have something in common: both live in a world that is different from that which exists for everyone else. He also wrote, “Talent hits a target no one else can hit. Genius hits a target no one else can see.”

The last quote applies to David Bowie‘s career; however, the former best describes the period when he recorded the brilliant Station to Station, which celebrates its 45 years in existence this week. This album has long been a favorite of mine and appears on my list of 20 albums I can’t live without.

In 1975, as a fifth grader, I was aware of who Bowie was, but a lot of his music didn’t cross my radar. That November, it all changed when I saw him appear on Soul Train. Bowie sang “Fame” and the song that got me interested in him, “Golden Years.” My young musical mind had not yet matured, so it would be several years before purchasing Station to Station. Over the years, I’ve had to replace that copy several times for the usual reasons: lent out and never returned, severely scratched, and theft. Whenever the album would go missing, I immediately replaced it because I did not want any time to pass without it in my collection.

Whenever I play Station to Station, I can’t help but listen to the whole thing without any interruptions. Musically, it takes a slight step away from Young Americans (1975), which Bowie described as “plastic soul,” and serves as a prelude to his Berlin trilogy (1977’s Low, 1977’s Heroes, and 1979’s Lodger). The album also introduces what would later prove to be his last stage persona/alter ego, the Thin White Duke, described in David Buckley’s book Strange Fascination: David Bowie The Definitive Story as an “amoral zombie.”

Bowie’s heavy cocaine and amphetamine use during the Young Americans sessions continued during the recording of Station to Station. He described this period as “singularly the darkest days of my life.” Despite his drug use, Bowie managed to pull himself together long enough to assemble a killer band to record the album. He enlisted guitarist Carlos Alomar, who played on the Young Americans album, drummer Dennis Davis, bassist George Murray, keyboardist Roy Bittan (E Street Band), and guitarist Earl Slick. Alomar continued to work with Bowie until the early 2000s.

What continues to amaze me is how this album got made considering Bowie’s drug use, but it never interfered with the work, according to Alomar. In an interview with Alan Light of Rolling Stone, he said, “When we were in work mode, it was always about the work. If it was fueled by coke or by whatever, David was always able to manage the decision-making. That professionalism was what enabled him to keep going.”

Station to Station starts with the title track, which introduces us to the Thin White Duke. If anyone ever asks you to find a song that references cocaine, the Kabbalah, and the occult, point them in this direction. Coming in at ten minutes and fourteen seconds, it’s the longest studio track Bowie has ever recorded. It’s almost two songs in one, with the first five minutes and fifteen seconds sounding like something you would hear from a German electronic band and the rest sounding like art rock meets disco mashup. The end of the song sets us up nicely for the next track, which is the previously mentioned “Golden Years.” When you hear it, you immediately think it could have easily been on the Young Americans album.

The story of “Golden Years” is an interesting one. Bowie’s first wife, Angie, and singer Ava Cherry claimed to be the inspiration for the song, but Bowie has stated that he wrote the tune for Elvis Presley, but it never came to be. In a 2002 interview with Blender magazine, Bowie set the record straight. “Apparently, Elvis heard the demos, because we were both on RCA, and Colonel Tom [Parker, Presley’s manager] thought I should write Elvis some songs,” he explained. “There was talk between our offices that I should be introduced to Elvis and maybe start working with him in a production-writer capacity. But it never came to pass. I would have loved to have worked with him. God, I would have adored it. He did send me a note once. ‘All the best, and have a great tour.’ I still have that note.” That would have been an interesting pairing. You can almost hear Presley sing “Run for the shadows, run for the shadows / Run for the shadows in these golden years.” Without question, it’s one of rock’s most significant “what ifs.”

Side one closes with one of the most beautifully written songs in Bowie’s catalog, “Word on a Wing.” Written during the filming of the movie The Man Who Fell to Earth, he composed what I consider to be a desperate cry for help and an acknowledgment that he needed it. The lyrics are of a tortured soul who is desperate for a lifeline: “I’ll never stop this vision flowing / I look twice and you’re still glowing / Just as long as I can walk / I’ll walk beside you, I’m alive in you / Sweet name, you’re born once again for me / And I’m ready to shape the scheme of things.”

Bowie managed to fit in almost every aspect of the human condition with the first three songs on Station to Station. Side two opens with “TVC 15” featuring a Professor Longhair-styled piano riff by Roy Bittan, which plays throughout the song. For the last 45 years, I had no idea what the hell this song was about. Through an internet deep dive and a couple of Kindle purchases, I finally discovered the origins of “TVC 15.” An occurrence inspired the song at Bowie’s home where a hallucinating Iggy Pop believed that a TV set swallowed his girlfriend. Bowie took this incident and created “TVC 15,” where the protagonist’s girlfriend crawls into a TV, and he decides to go in after her. This strange but delightful tune is a great open to side two and one of the more underappreciated songs in Bowie’s catalog.

“Stay” is arguably the funkiest tune on Station to Station and could also have been on the Young Americans album. Earl Slick’s guitar work is the co-star of this song, along with Bowie’s vocals. “Stay” remained a staple of Bowie’s live performances throughout his career.

Rounding out Station to Station is “Wild is the Wind,” a hauntingly beautiful song initially recorded by Johnny Mathis in 1958 for a movie of the same title, but later flawlessly covered by Nina Simone in 1966. Bowie struck up a friendship with Simone after meeting her at a private club called Hippopotamus in 1974. As she was leaving, he called her over to his table, and they chatted and exchanged numbers. For about a month afterward, they spoke on the phone daily and talked about what it meant to be an artist who was different from everyone else. He gave her the encouragement she needed at the time, and she saw him for who he was. In her biography What Happened, Miss Simone, she is quoted as saying, “He’s got more sense than anybody I’ve ever known,” she said. “It’s not human—David ain’t from here.” This friendship led Bowie to record “Wild is the Wind” as an homage to his friend. It is one of the most moving songs in his discography and a great end to Station to Station. Check out the incredible version he performed at the Yahoo Internet Awards in 2000.

Considering all of the personal turmoil Bowie was enduring when he recorded Station to Station, it’s miraculous that this six-track album remains one of the most important and influential albums recorded in the last 50 years.